The Ontario Court of Appeal recently considered another potential “mutual driveway situation. In English v. Perras, 20 July 2018, the Court decided that the evidence was insufficient to establish the claim.

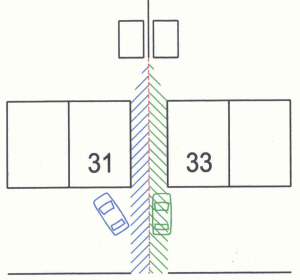

The two Ottawa residential properties 371 Third Avenue and 373 Third Avenue were side by side with a 14 foot strip of land running between the two houses. The contentious strip accessed garages at the rear.

The two houses were built in 1928. Mr. English bought 371 in 1980. Mr. Perras bought 373 in 2003. Mr. English saw a survey when he bought which showed a mutual driveway. The survey was commissioned by the previous owner for the purpose of the sale.

A few weeks after the survey was prepared, on February 26, 1980, the predecessors in title to both properties entered into an agreement concerning the abutting driveways. The Agreement was limited to 21 years, less a day and expired in February of 2001, just over two years before Perras acquired the adjoining property.

Perras proposes to erect a fence along the property line. He would access the rear just from his side alone. This is complicating for English because he has a small retaining wall in the front of his house which would block his access. He needs to come up on the 373 property side.

The “key” witness for Mr. English was Brian MacNamara. His parents purchased 373 Third Avenue in 1957, and his mother sold the property to Perras in 2003.

Mr. MacNamara lived at 373 continuously between 1957 and 1976, and then visited about once a month from 1976 to 1979, while he was in school.

In order to establish an easement, a claimant must satisfy the following four essential characteristics of an easement or right-of-way:

i. There must be a dominant and servient tenement;

ii. The dominant and servient owners must be different persons;

iii. The easement must be capable of forming the subject matter of a grant; and

iv. The easement must accommodate – that is, be reasonably necessary to the better enjoyment of – the dominant tenement.

The Court stated:

[28] The doctrine of lost modern grant is recognized as a method for acquiring a prescriptive easement. It involves requirements in addition to the constituent elements of an easement.In 1043 Bloor Inc. v. 1714104 Ontario Inc., 2013 ONCA 91, 114 O.R. (3d) 241, Laskin J.A. described the doctrine in the following way, at para. 91:

[T]he acquisition of a prescriptive easement by lost modern grant rests on a judicial fiction. The law pretends that an easement was granted at some point in time in the past but that the grant of the easement has gone missing. A prescriptive right emerges from long, uninterrupted, unchallenged use for a specified period of time – in Ontario, 20 years… [29] In Ontario, there are certain restrictions on prescriptive easements; they have been abolished with respect to properties registered in the Land Titles system: and Titles Act, R.S.O. 1990, c. L.5, s. 51.Consequently, the 20-year period must precede the transfer of property into the Land Titles system.

In this case, both properties were registered in the Land Titles system in 1996.

Accordingly, Mr. English…. was required to prove “uninterrupted and unchallenged use” for any 20-year period before 1996: see Kaminskas v. Storm….

And, the Court further indicated:

[32] The outcome of this case should not be understood as an endorsement of the Perras’ aggressive conduct in erecting the fence.It is not behaviour that is worthy of reward. Quite the contrary.

Nevertheless, in this case, it is the conduct of the predecessors in title during the putative prescriptive period (1957 to 1979) that matters, not that of the present-day owners. I turn now to the prescriptive period.

(2) Land not used as of right

[33] The key issue in this case is how to characterize the use of the land during the prescriptive period.As Laskin J.A. noted in the above-quoted passage of 1043 Bloor Inc.,

the use must be “uninterrupted and unchallenged” throughout the 20- year period. And the use must be “as of right”, not by permission.

………………..

[36] In this case, the evidence did not establish anything more than permissive use during the prescriptive period.At best, the evidence showed that the occupants of 371 and 373 permitted each other to cross the property line as they went to and from their parking spots.

There was no evidence that the occupants of either dwelling did so as a matter of right…

………………..

[40] The Agreement was compelling evidence that the use during the prescriptive period was by way of permission.………………..

[42]……. The fact that the Agreement was entered into at all was compelling evidence that the predecessors in title had been acting as good neighbours in permitting incursions on each other’s property. [43] The question before the application judge was not whether the easement had winked out of existence; it was whether it existed in the first place. The fact that the Agreement was entered into at all was compelling evidence that the predecessors in title had been acting as good neighbours in permitting incursions on each other’s property.Finally, the appeal was allowed, there was no easement established. Perras was awarded $20,000.00 for the motion and $10,000.00 for the appeal.

COMMENT

This became a rather expensive undertaking for both parties. They each have to pay their own respective lawyers and English has to pay Perras another $30,000.00.

Interesting point of principle! How much would it have cost to remove two feet of a small retaining wall instead?

Further, notice that the two neighbours really cannot offer any valuable evidence. Who cares what they said or did! The relevant issue was the conduct of the predecessors in title. The relevant time frame was while the property was registered in the Registry system before transfer to Land Titles. That took place in 1996. So, we need to look at the conduct of the two adjoining owners for any 20 year period of time prior to 1996. Anything after that, is not relevant.

Thus, for this type of dispute, the evidence will come from people who used to live there.

It is important to remember that a prescriptive easement is “theft” of property from the rightful owner. You can’t steal something if you have permission.

What certainly didn’t help was a 21 year temporary agreement giving “permission”. That looks like consent. That takes us back to 1980. Basically, we would need proper evidence for 1960 to 1980. But, clear and unmistakable evidence was not available for that time period.

Let’s look at that situation a little more closely. Why wasn’t it 21 years or 50 years, or in perpetuity? The reason was that anything 21 years or more would have required the Consent of the local Committee of Adjustment. This would likely have delayed the closing and have cost several thousand dollars. However, had that taken place, we would not have an issue today.

Further, if the parties were to stick to the 21 years less a day, they should have recognized that an easement had been acquired by prescription. They should have made proper references to that in the recitals. This didn’t take place, so there was “no evidence” and without evidence the claim for an easement is not going to be successful. Careful drafting of the Agreement would have helped. In addition, the survey could have been attached, and accepted by the parties as accurately reflecting a mutual driveway. There were some potential solutions at hand. It would have been preferable to solve the issue for once and for all.

The real problem here was that 21 years rolls by very quickly.

Brian Madigan LL.B., Broker