Just what is it and where does it come from? In English common law, the concept seems to have lost its meaning. Not too many people seem to know what it means, just legal scholars and historians have an interest in the subject.

Today, there are really two different definitions of the term, and it depends upon whether you are discussing public or private property.

In respect to public property, the concept has ancient origins actually predating the common law and the feudal system in the Middle Ages.

Property which was occupied and held by force against others was held in “allodium”. Basically, that means “without any restriction, of any kind or nature, whatsoever”. People would come across unoccupied, vacant land and would simply make it theirs. There was no one around, no one to say that they could have it, no one to grant permission, no one to sign a deed. In this regard, “might was right”. If you had the property, and could defend it against others, then it was yours in “allodium”. Since there was no place to register your title, it was simply acknowledged that you held allodial title. That simply meant that you had no deed.

To a certain extent, the concept of “allodial title” is just a legal fiction. It doesn’t really exist in the legal system. It is simply a method of comparing it to other properties and helping to understand the differences between it and “fee simple”.

So, let’s have a quick look at the feudal system from medieval times. The King owned all the land. He leased it out to his tenants, and they sub-let it to others and so on, in a grand pyramid scheme. You definitely would want to be near the top.

In 1066, William the Conqueror, from France succeeded in the Battle of Hastings. He made significant changes to the feudal system, and by 1215, the first (of a series) of Magna Cartas was passed. This restricted the role of the King and is considered to be the first constitution of England. Within the next century, substantial changes were made to the property system. Tenure gave way to estates. So, rather than “leasing” land from the King, people who occupied land were considered to hold some ownership rights (estates) in the land. The estates could be restricted or limited in some way. It could be present or future. It could be temporary (a leasehold estate) or it could be full ownership with all the “bells and whistles” that go with that. This kind of estate was referred to as “fee simple”. This was the highest estate that anyone could have. It was subject to certain rights in favour of the King, but other than that, it was completely unrestricted.

Basically, there were four rights retained by the King. A property would be:

1) subject to the right of the King to require servitude from the property,

2) subject to the right of the King to repossess the property,

3) subject to the right of the King to inherit the property, and

4) subject to the right of the King regulate the property.

These are now sometimes referred to as taxation, expropriation, escheat and eminent domain.

So, in the English common law system, an estate in fee simple is as good as it gets. But, you had to get this estate from somewhere! In fact, you got it originally from the King. There was a Deed or a grant. There was an actual piece of paper that was “evidence” of your ownership. The only way that could happen is if you had a legal system and everyone agreed to go along with the rules.

Now, let’s go back to our concept of allodial title. First, there is no one around. The place is vacant. You could probably go an entire lifetime without ever seeing anyone other than from your own family or clan. Land is not scarce, people are. There is no legal system. There is no registry office. No one keeps records of anything. So, to have allodial title is simply to own your land by occupancy.

Actually, the only way that you can hold title this way is if you are a country. There are no deeds. Other countries simply accept that they will not claim your land, since you are likely to defend it.

There is one other concept of allodial title, but it applies to private ownership. To a certain extent, it is just an historical concept. Land that was “unowned” perhaps in the wild west prior to settlement, or perhaps native or aboriginal lands that were occupied prior to the European immigration in the 16th century.

There are just a few states and none of the provinces that continue to maintain a concept of allodial title. Most have abolished the concept. At best, it was really pseudo-allodial title. It was possible to receive a grant in favour of a person specifying allodial title. Recently, the State of Nevada will permit such a grant in limited circumstances provided the individual pays up their property taxes in advance. But the concept of a grant is foreign to the concept of allodial ownership.

Allodial title is completely free and clear of all obligations, liens, encumbrances, taxes, mortgages and the like. However, where it is still recognized either historically, or presently it is still a rather pseudo-allodial title since the four basic restrictions that apply to fee simple ownership, apply to it as well: taxation, expropriation, escheat and eminent domain.

Any restrictions whatsoever, any recognition of a superior, granting institution would be fully alien to such a concept. Allodium simply means occupation of lands without challenge. This must imply to a certain extent: wilderness lands. So, that means the moon and the planets are up for grabs. Just get there first! And, be sure to bring s flag!

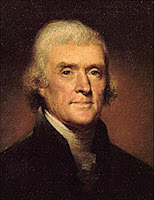

I thought that I might provide you with an excerpt from an apologist who authored a justification for reprisals against a King who wanted to exert his ownership over lands which the author felt were held “in allodium”. The author is much more familiar with the concept of allodial title than I, and offers something of an insight into the rights of property ownership as we understand them today.

“That we shall at this time also take notice of an error in the nature of our land holdings, which crept in at a very early period of our settlement.

The introduction of the feudal tenures into the kingdom of England, though ancient, is well enough understood to set this matter in a proper light.

In the earlier ages of the Saxon settlement feudal holdings were certainly altogether unknown; and very few, if any, had been introduced at the time of the Norman conquest.

Our Saxon ancestors held their lands, as they did their personal property, in absolute dominion, disencumbered with any superior, answering nearly to the nature of those possessions, which the feudalists term allodial.

William, the Norman, first introduced that system generally. The lands, which had belonged to those who fell in the battle of Hastings, and in the subsequent insurrections of his reign, formed a considerable proportion of the lands of the whole kingdom. These he granted out, subject to feudal duties, as did he also those of a great number of his new subjects, who, by persuasions or threats, were induced to surrender them for that purpose.

But, still much was left in the hands of his Saxon subjects; held of no superior, and not subject to feudal conditions. These, therefore, by express laws, enacted to render uniform the system of military defense, were made liable to the same military duties as if they had been feuds; and the Norman lawyers soon found means to saddle them also with all the other feudal burthens.

But still they had not been surrendered to the king, they were not derived from his grant, and therefore they were not holden of him. A general principle, indeed, was introduced, that “all lands in England were held either mediately or immediately of the crown,” but this was borrowed from those holdings, which were truly feudal, and only applied to others for the purposes of illustration.

Feudal holdings were therefore but exceptions out of the Saxon laws of possession, under which all lands were held in absolute right. These, therefore, still form the basis, or groundwork, of the common law, to prevail wheresoever the exceptions have not taken place.

America was not conquered by William the Norman, nor its lands surrendered to him, or any of his successors. Possessions there are undoubtedly of the allodial nature.

Our ancestors, however, who migrated hither, were farmers, not lawyers. The fictitious principle that all lands belong originally to the king, they were early persuaded to believe real; and accordingly took grants of their own lands from the crown.

And while the crown continued to grant for small sums, and on reasonable rents; there was no inducement to arrest the error, and lay it open to public view.

But his majesty has lately taken on him to advance the terms of purchase, and of holding to the double of what they were; by which means the acquisition of lands being rendered difficult, the population of our country is likely to be checked.

It is time, therefore, for us to lay this matter before his majesty, and to declare that he has no right to grant lands of himself. From the nature and purpose of civil institutions, all the lands within the limits which any particular society has circumscribed around itself are assumed by that society, and subject to their allotment only.

This may be done by themselves, assembled collectively, or by their legislature, to whom they may have delegated sovereign authority; and if they are alloted in neither of these ways, each individual of the society may appropriate to himself such lands as he finds vacant, and occupancy will give him title.

That in order to enforce the arbitrary measures before complained of, his majesty has from time to time sent among us large bodies of armed forces, not made up of the people here, nor raised by the authority of our laws: Did his majesty possess such a right as this, it might swallow up all our other rights whenever he should think proper.

But his majesty has no right to land a single armed man on our shores, and those whom he sends here are liable to our laws made for the suppression and punishment of riots, routs, and unlawful assemblies; or are hostile bodies, invading us in defiance of law.

When the course of the late war it became expedient that a body of Hanoverian troops should be brought over for the defense of Great Britain, his majesty’s grandfather, our late sovereign, did not pretend to introduce them under any authority he possessed.

Such a measure would have given just alarm to his subjects in Great Britain, whose liberties would not be safe if armed men of another country, and of another spirit, might be brought into the realm at any time without the consent of their legislature.

He therefore applied to parliament, who passed an act for that purpose, limiting the number to be brought in and the time they were to continue. In like manner is his majesty restrained in every part of the empire. He possesses, indeed, the executive power of the laws in every state; but they are the laws of the particular state, which he is to administer within that state, and not those of any one within the limits of another.

Every state must judge for itself the number of armed men, which they may safely trust among them, of whom they are to consist, and under what restrictions they shall be laid.

To render these proceedings still more criminal against our laws, instead of subjecting the military to the civil powers, his majesty has expressly made the civil subordinate to the military. But can his majesty thus put down all law under his feet? Can he erect a power superior to that which erected himself? He has done it indeed by force; but let him remember that force cannot give right.”

The comments noted above were offered by Thomas Jefferson as a justification for the Boston Tea Party and the American Revolution.

But, you have to admit that he certainly did understand and appreciate the concept of allodial title.

Brian Madigan LL.B., Broker